We’ve become familiar with the terminology climate control as applied to heating, cooling, and ventilation of car cabins, and we’re well aware that the heat, when needed, comes from engine heat, and that the cooling, again when needed, comes from a form of refrigeration. That inevitably uses power drawn from the engine to operate the compressor, condenser, and pumps involved. With battery electric cars (BEVs) there’s relatively little heat generated by the drive unit, so any other power requirements for cooling and heating necessarily draw on battery capacity and thus affect the car’s range. You can, of course, preheat the cabin, or cool it, whilst it is plugged into a charger. Once on the road though, the climate control system depends largely on the energy in the power battery, or any other waste energy sources that can be tapped into. The best way to turn these limited resources into useful heating or cooling is by using a Heat Pump, which was first used by Nissan in their Leaf model, back in 2013, creating a lead followed by other manufacturers, albeit that Tesla arrived somewhat late on the scene. Heat pump technology, as we know, is now a growing feature of home heating and cooling, offering significant energy savings.

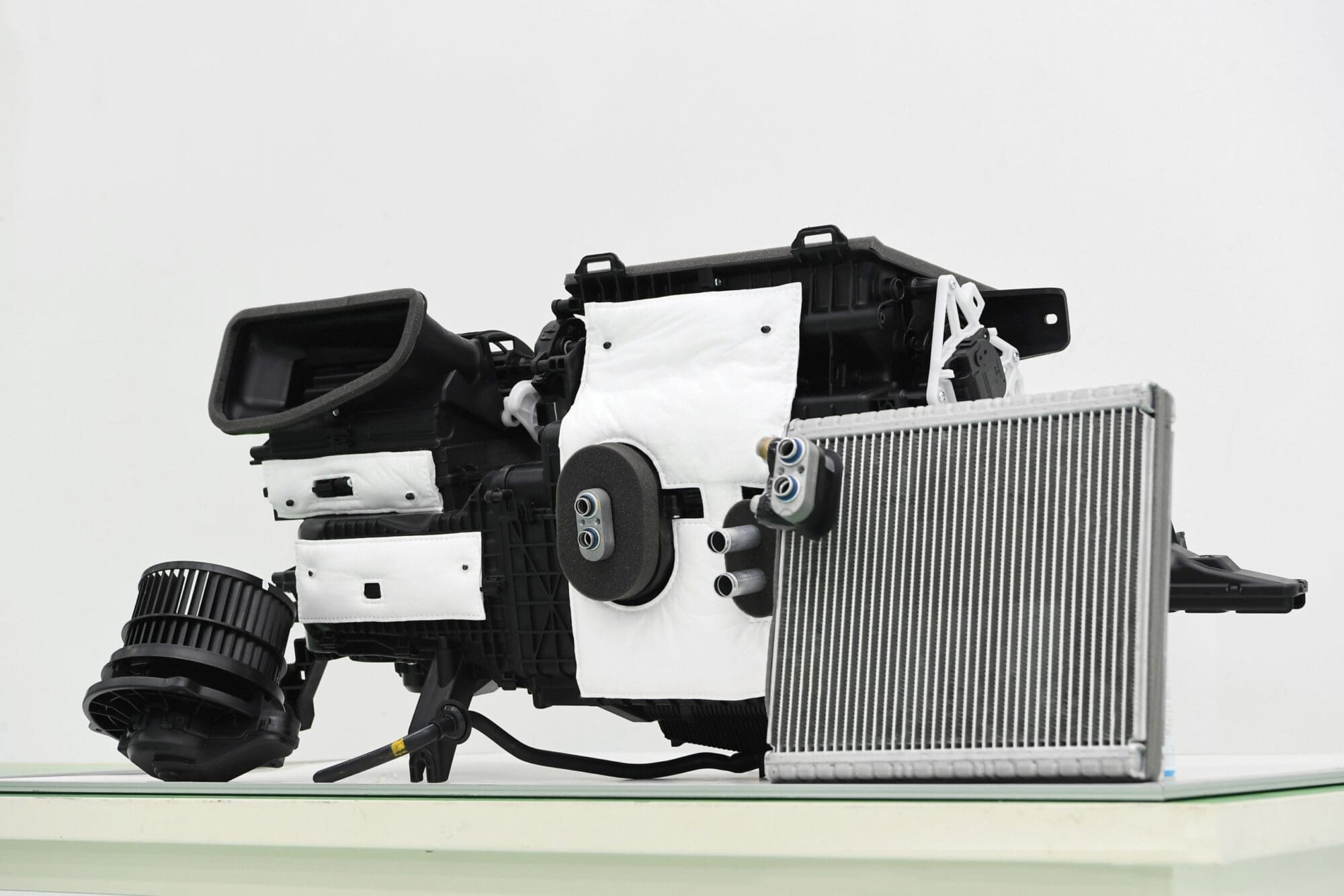

The electrical components of heat pump-based systems can, in good conditions, transfer three times as much heat to, or from, the cabin as the energy they use. Not only is it helpful in terms of battery energy savings, but drawing on such available heat sources becomes a critical part of the car’s overall “thermal management system”, involving cooling or heating the battery, and cooling other electrical components like the charging unit, and the inverter. Critical to preserving the life of the traction battery is maintaining its temperature in its optimum operational range. In many BEVs, liquid battery cooling circuits are linked to the heat pump system, which is the most efficient way of cooling during fast charging. It is far more efficient than air cooling, as is used in some less costly BEVs, and reduces battery dimensions by up to 35 per cent compared with air cooling. The circulating liquid coolant is kept cool not by using a draught-cooled liquid/air radiator, but with a liquid/liquid heat exchanger that cools using the heat pump refrigerant.

How big a difference can heat pump systems make to the battery range and other issues? Tests on the Hyundai Kona Electric and Kia Niro found that their heat pump systems significantly reduced battery consumption in very cold conditions. Driven in temperatures of minus 7 degrees Celsius, and with the climate control system activated, the systems were able to maintain 90 per cent of their driving range compared to journeys made at an ambient 26 degrees Celsius. Other non-heat pump BEVs tested saw driving ranges drop by 20 to 40 per cent in the same test conditions. By contrast, in hot ambient conditions, and when fast charging is used, simple air-cooled batteries may struggle to keep the battery within the required safe temperature band. After one fast charge session, and when cruising at higher speeds, the whole power pack may become hot, without heat pump assisted liquid battery cooling, with further attempts at fast charging being rejected until the battery has suitably cooled down. This situation is rarely encountered at sub-motorway speeds though, and only with high charging rates.

We should mention another aspect – the pre-conditioning functions that are offered for BEVs. The advantage of pre-conditioning is that, when you’re ready to drive off, the cabin is already heated, or cooled if necessary, and the windows cleared, using the heat pump and the ventilation circuits. Plugged in to the charger, the energy required comes direct from the grid, and the energy stored in the battery is unaffected if already at its maximum. Your comfort, and good vision, with demisted windows, comes without affecting the driving range, and the thermal management system will, in some cars, be used to electrically preheat a cold battery to maximise efficiency and power delivery at low temperatures.

© Motorworld Media 2023

Registered Office: 4 Capricorn Centre, Cranes Farm Road, Basildon, Essex. SS14 3JJ

Company Number: 8818356

Website designed by Steve Dawson